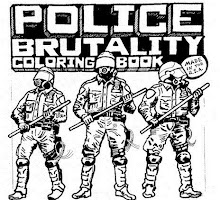

“Call Flooding” For Police Reform

With change most likely to come

on the heels of public demand so strong that it can’t be ignored, the public is

encouraged to flood police departments with calls to end police brutality.

By Katie Rucke

Since the advent of social

media, the public’s relationship with law enforcement has evolved into one in

which the public can instantly call out abusive policing techniques and

incidents in the hope that unlawful and inappropriate behavior can be stopped

once and for all.

It may not be glaringly

obvious, but the use of social media channels such as Twitter has been instrumental

in garnering public support for reversing law enforcement’s military-esque and

trigger-happy procedures that have become evident during several events

throughout the years, such as the 2012 shootings in Anaheim, Calif., to the

more recent shootings and calls for reform in Albuquerque, N.M.

While not every call for reform

is answered or even acknowledged, many demanding widespread reform and an end

to police brutality argue that posting concerns on social media and “call

flooding” police departments are important steps in demonstrating to the law

enforcement community that the American public will not tolerate abusive

tactics. It also warns law enforcement that their abusive and unlawful

practices are not going unnoticed.

For example, last month when

the New York Police Department announced a Twitter campaign known as #myNYPD,

asking New Yorkers to post presumably positive photos and interactions with

officers, many police reform advocates used the campaign as an opportunity to

showcase poor police tactics.

The pro-police campaign quickly

turned into a PR nightmare for the department, as thousands of photos of NYPD

officers demonstrating arguably brutal tactics such as beating restrained

individuals, pulling the hair of a handcuffed woman, and shooting and killing

innocent bystanders, flooded the Internet.

The way Internet users turned

the campaign on its head was viewed as such a success that many police reform

advocates took it as a chance to call out other departments for wrongful

behavior. The Los Angeles Police Department, for example, got slammed under the

hashtag #myLAPD.

Although the social media

campaign didn’t go as planned, NYPD Police Commissioner Bill Bratton said he

welcomed the bad photos, explaining that sometimes the work police officers do

“isn’t pretty.”

However, Bratton didn’t have

anyone post any of the “bad” photos on the department’s Facebook page, which is

what officials decided to do with some of the “good” photos.

That’s the thing with social

media — although thousands of people may have posted pictures of NYPD officers

engaged in police brutality tactics, none are currently visible, since the

police departments often delete posts that don’t paint them in the finest

light.

Some are outraged to learn the

police department actively deletes these negative posts, but some police reform

advocates argue that deleting the posts is OK because someone at the department

at least had to take the time to read the message and then delete it.

In other words, the message

that it is time for a change was heard loud and clear, even if it was later

deleted.

While not all Americans

exercise their right to call a police department in order to report

inappropriate behavior by officers, it’s completely legal to do so and is

protected under the First Amendment — as is posting one’s grievances on social

media channels.

But it’s important to remember

that an individual is only protected so long as they remain calm. An angry

tirade in which an individual mocks, condemns, accuses or judges officers is

not protected, and it may result in an individual’s concerns not being taken

seriously. A heated exchange with law enforcement that includes profanity and

threats will also likely hurt other people’s attempts to reform law

enforcement’s procedures and policies, as local police departments often report

irate callers using abusive or profane language for harassment to other local

law enforcement agencies and sometimes even the FBI.

Groups such as Cop Block, Honor

Your Oath, the National Police Misconduct Reporting Project and Photography Is

Not A Crime, have spent years educating the American public on a variety of

police-related interactions — from what a driver should do if he or she is

pulled over at a checkpoint, to what a citizen’s rights are when video and audio

recording interactions with police officers.

Acting as a voice for the

public, these groups have called directly for reform, but have also educated

the public on why reform is necessary and how the public can participate. But

like any other political issue, real reform likely won’t come until the public

overwhelmingly demands change.Concerned about the emergence of a growing police

state throughout the United States, groups are now calling for Americans to

flood police departments with calls for police reform.

The public is asked to “call

flood” not only law enforcement officials, but also local elected officials,

such as mayors and city councils, local media outlets and even the local

chamber of commerce, since as police reform advocate Mike Murphy wrote, “[I]f

ever there’s a group sensitive to a community’s public image, it’s the local

chamber of commerce.”